January Reading

A memoir, a 100-year-old novel, a 2025 debut, and a book of writing theory

A confession. Some of these volumes were read in the tail end of last year (meaning I’m lying to you in the title) but I wanted to share more about these reads with you, here, in addition to the cute book photos and copious underlined passages in my stories on Instagram.

On New Year’s Day, I met my friend Harri at Old Street tube stop and, after a quick detour into a cafe for lattes to go, headed to Hampstead Heath. The Heath, for those who have never been, is one of the largest public green spaces in London and, naturally, remains common land only due to the efforts of ordinary people, who clubbed together to defend it from private interests. We celebrated New Year with a frosty walk so long we wondered if we had strayed into the Home Counties, and, then, a Bun Cha Ha Noi (tradition) at a Vietnamese place on Dalston High Street. Afterwards, I walked home by the light of a nearly full waxing moon to begin the debut novel from Lidije Hilije.

Do you like the cold? I didn’t used to, but something came over me last winter, and now I love it. It’s very strange—I have even rejected summer. Too hot to function. Typically a compliment, but not to summer 2025. I think I preferred it when I lived by the sea and could cool off twice a day with a swim. The winter feels like someone breathing sharply against my neck or touching me—the negative space around me so filled by a cold so visceral it feels like being held. I was thinking about this the other day, a lack of touch. Gripping the wooden bannister as I descended the stairs and trying to think of the last time I have been hugged for more than a few seconds.

In Slanting Towards The Sea, Lidija Hilje writes about how we need seven hugs a day to live. As minds go, this leads me to mentally replay the scene from Practical Magic, when Sandra Bullock writes to her sister (played by Nicole Kidman) on a night bright with moonlight, “I feel there is a hole inside of me. And emptiness that at times seems to burn.” The letter ends, “there is no man, Gilly. There is only that moon.”

It seems like all of the books I have read recently, and will recommend to you, talk about emptiness, unluck, and living with the hole that’s left in a life where love goes unfulfilled. Even my last recommendation, an Ursula K. Le Guin essay on writing theory, published as a slim volume by cosmogenesis in 2024, is about how to write about life in a way that helps and heals.

I’m curious about you, reading this newsletter—what was your first read of the year? Have you read any of the following books? Would you?

Mother Mary Comes To Me by Arundhati Roy

Firstly, let’s make sure to note that this is one of the most physically beautiful book I have ever owned. Published by Penguin, the edition I read was a red hardcover, slightly wide format, with a lovely slip of white paper around it (like… a quarter of a dustcover?) with black and white photos of a past and then present Arundhati Roy.

The memoir doesn’t focus, as you might expect, on her career as a writer, but the life she has lived around it, the two novels featuring as unusual blips within the narrative of her ‘usual’, which is to say an interesting, political, thoughtful life.

I had no idea Roy was such a provocateur in her own country, nor that she had received death threats for some of her published articles. I’m not going to pretend that I understand the politics of 20th-21st century India however, after reading this memoir, I know much more than I did, and I enjoyed that! (Remembering any of it is its own issue.)

Arundhati comes across as a very honest memoirist. She doesn’t leave much out and because of that it feels like you’re getting the truth of a life—in some years, not much happened, and she will mention that. We walk with her. We don’t leap over portions of life, dragged by an insistent, dictatorial authorial hand. The narrative she chooses to build this work around is instead a rather static one—that her mother is a difficult person who was wilful, harsh, dismissive, in their relationship; who didn’t love her as other mothers love.

Complicating the issues, her mother is also brilliant; the founder of a school which transforms education in Kerala and seemingly worshipped by many who encounter her

What she’s saying is, you think I’m extraordinary, but I’m going to show you how I’m the type of sapling that grows out of this crazy kind of muck. Basically, “this is how you raise a writer like me, and I’d advise you against it.”

Reading this book made me feel tender towards Arundhati. Because what I took away from it was that, through everything she went through with her mother, Roy still has so much heart for her. So much compassion and love.

My mind is wandering again. Have any of you seen Robert Redford’s adaptation of A River Runs Through It? Based on the novel by Norman Maclean, who writes of his alcoholic brother, played by Brad Pitt at peak cute:

“But we can still love them. We can love them completely, without complete understanding.”

Other notes: Delhi and Kerala are the main settings (I really enjoyed the busy city setting of Delhi). Roy has two bestselling novels I’ve never read (tell me—should I?) called The God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. The former won the Booker Prize in 1997.

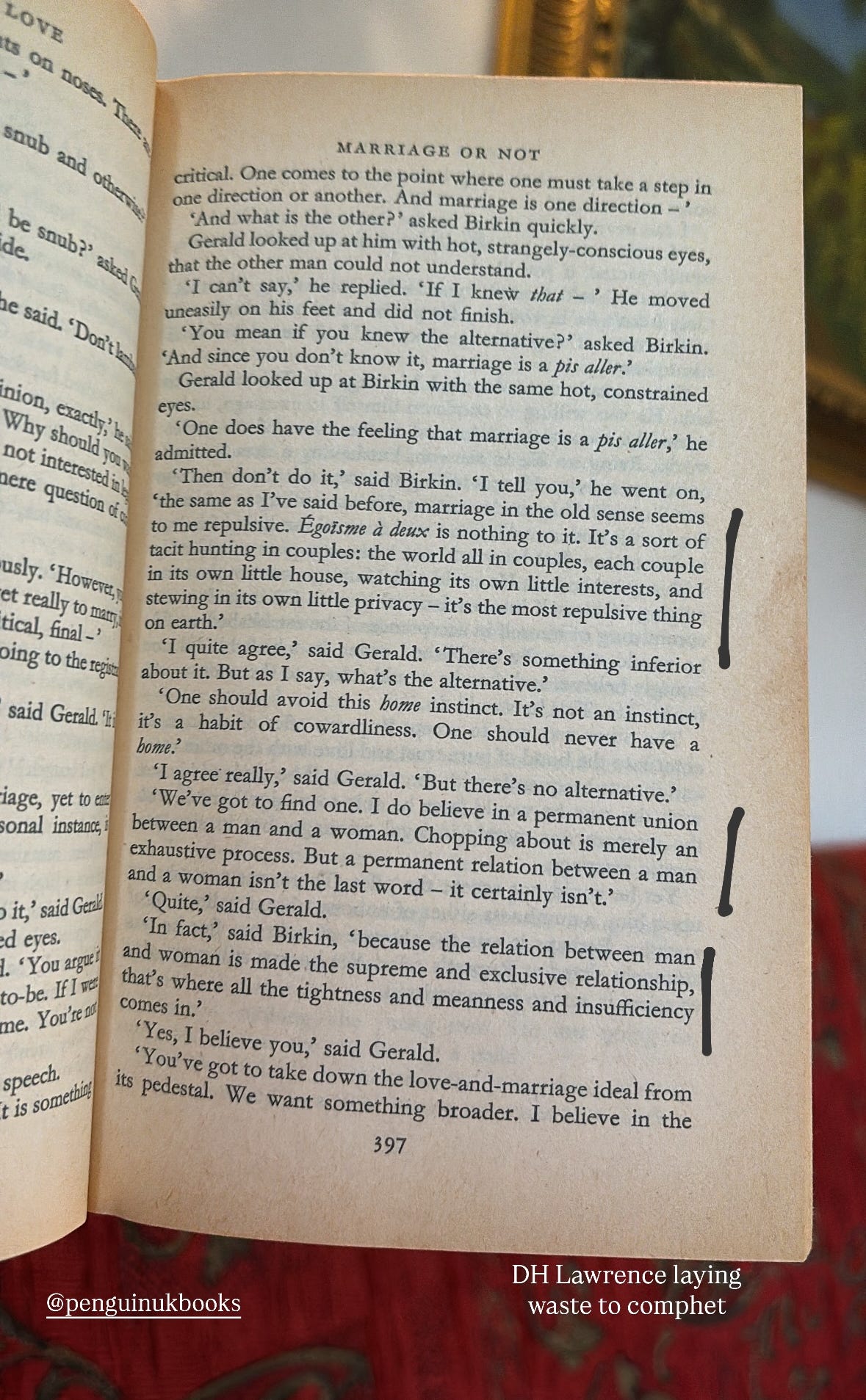

Women in Love by D H Lawrence

I have a tendency with classics to dismiss them before imbibing. I remember doing this with Breakfast at Tiffanys, a delightful film which ranked in my top five of all time for years.

Note for the physical book nerds (is there a word for this?): my edition of this book was borrowed from my dad (I thought it was from my pal Coralie Colmez, but I was mistaken. It was so her, and she always gives great recommendations). This is a Penguin paperback, 1969, and I think my reprint of it dates to around 1973 (I’m writing this in London and it went back to my parents in Lincolnshire for Christmas and stayed. Penguin 70s-era paperbacks are like that—they have attitude and they’re cosy). I truly love pocket paperbacks and this was such an easy read specifically because I could carry it everywhere, easily, in my long coat or the inside pockets of my denim jacket. Why aren’t all books this? Hardbacks can be beautiful (they can also be ugly and pointlessly, prohibitively expensive) but it’s so much easier for me to enjoy something if I can stay hooked in the world, riding on the romantic countryside vibes, on the bus, in the park, on my bench drinking coffee, etc. I realised reading this that, also, the paper is thinner than in contemporary novels. My edition felt the size of Golden Boy or Cleopatra and Frankenstein; as a modern reader, I estimated it about 110,000 words, however, it’s actually about 180,000 words and printed on thin paper. More bang for your buck.

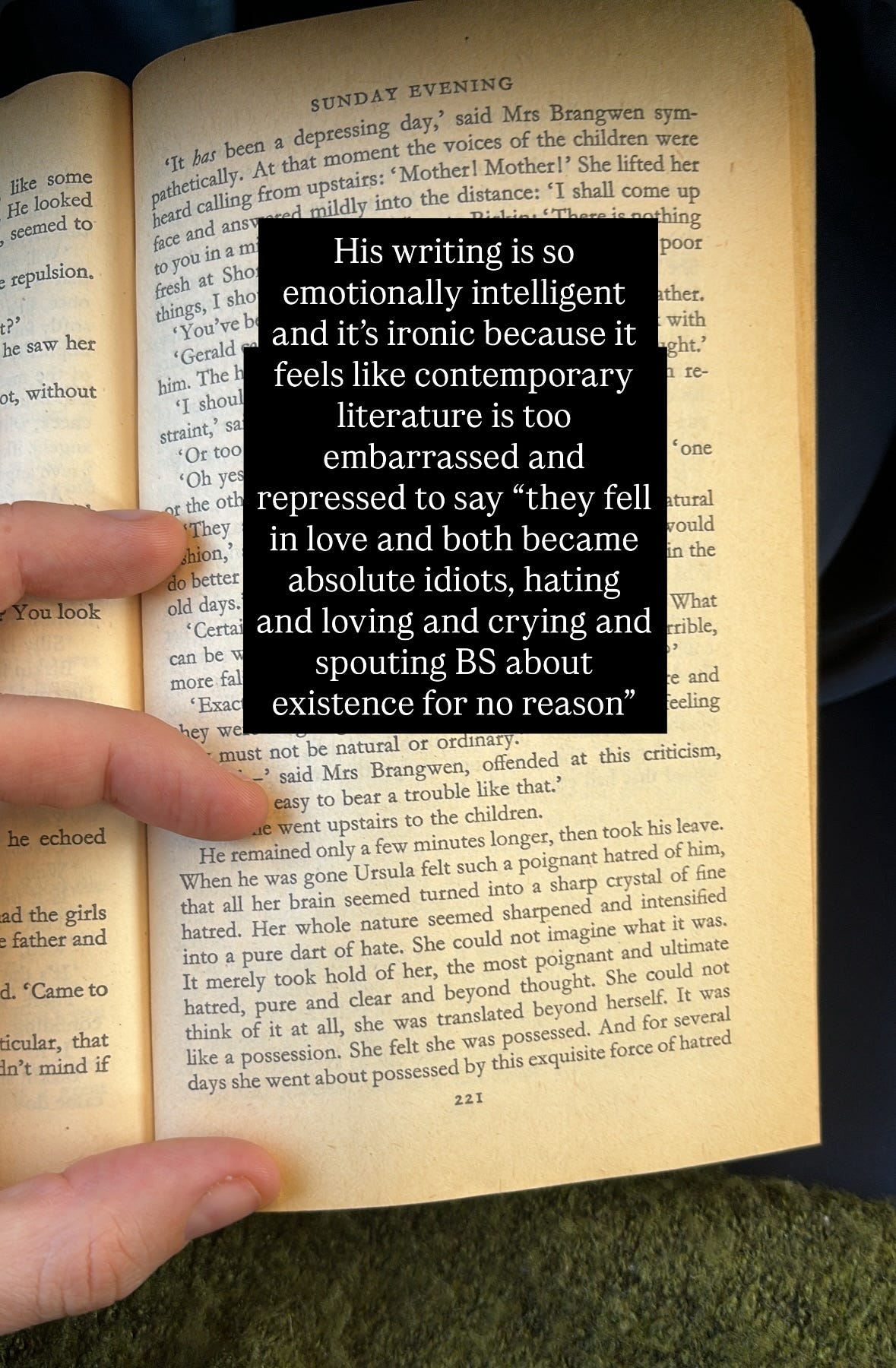

So, to the read. I cannot explain how bizarre this reading experience was. Written over 100 years ago, by D. H. Lawrence (D for David), the social mores could be 1980s. The novel is about two ‘old money upper class’ men and two ‘new, educated middle class’ women, all living in a village just outside Nottingham, most of whom bop down to London for a shag now and then.

Here’s me on Instagram with the sections that explain the whole book for me:

Also: I loved the setting, because it’s near where both sides of my family hail from and it made me realise I so rarely see the midlands in contemporary novels. It made me think if this was written now, it would be set somewhere else, somewhere known and aspirational. Like Cambridge.

David, the author, from Nottinghamshire, was born 11th September 1885. In the first photo of him that appears in an online search, he looks exactly how I imagined one of the two male characters in the book, Birkin (who I lowkey hated).

I’d like to plan more time laid on a sofa reading all day long, as 2025’s holiday reading session in front of the fire marked the second consecutive yule holiday I’ve added a book to my favourites list. Last year’s was Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistlestop Cafe by Fannie Flagg, this year’s was Women In Love.

Slanting Towards The Sea by Lidija Hilje

“ I cried because I was only 19 and I was already so tired of carrying around that jagged grain of loneliness on the inside that always threatened to cut me if I made a wrong turn. I cried because I had all this love inside me, and it had nowhere to go.”

Speaking of reading all day long, this is the first book I have read in a day since Christmas day 2024.

I’m sure you’ve seen it around bookstagram. It’s been a runaway hit on both sides of the Atlantic. Both versions of the cover are gorgeous. The Croatian setting was unique (in terms of my own reading, and rare amongst popular books) and it was interesting to learn about the changes there as the country developed over the lives of protagonists Ivona and Vlaho. But for me, this is a book about a topic close to my heart; one I struggle with and am writing about in my most recent books. How do we live, when we are wanting? How do we cope, when we know that wanting is permanent. Ivona is 38. My age. She cannot have children and she cannot have Vlaho, the love of her life, who is married to another woman.

Another theme developed as I read—convention interrupting fate. But what was unique here was that Hilje explored that convention through the characters psychology, illustrating how they inherited that psychology from the circumstances of their childhoods, family grief, small c conservatism, and parent dynamics. I’ve been talking about parent dynamics and inherited internal narratives in therapy for the last two years. Suffice to say, this chimed with me.

So as not to give more away, let me just add the Daunt Books blurb:

Ivona and Vlaho meet as students at the turn of the millennium in Zagreb. Everything smells of freedom and possibility. Red Hot Chili Peppers are pumping through the speakers of a bar in the city centre and cheap beer is overflowing; newly democratic Croatia is alive with hope and promise. They fall in love instantly.

A decade later, Ivona has returned to her childhood home in Zadar to look after her ailing father. She and Vlaho are divorced, yet she finds herself welcomed into his family life by him and his wife. But when a new man enters Ivona’s life, the trio’s carefully curated dynamic is disturbed, forcing a reckoning for all involved.

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin

This slim volume was lent to me by the folk musician Elanor Moss, who also grew up in Lincolnshire (although we met in London, living together in a ramshackle house we were forced to flee when the situation with the landlord proved too unstable). It’s £6.89 so, unless you’re flush, I wouldn’t urge you to buy it. If you are flush… fabulous! Support a small publisher and order it online.

This is an essay by the famous sci-fi writer Ursula K. Le Guin, in which she discusses her theory of written work. There ended up being a lot in there that I’ve always thought (for instance about endings), and it was nice to read my own percolations and ponderings articulate in such a succinct and clear way.

“The novel is a fundamentally unheroic kind of story,” she writes, adding, “a novel is a medicine bundle, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.”

This is exactly what I like to challenge myself to do these days, both in sense of theme and construction method. Thematically, my work is about how to go on living, how to restructure life, when things haven’t worked out the way you wanted them to, whether through tragedy or trauma or just the great incomprehensible trundle of living. Building the novel, it’s very important to me to find a structure for each particular book and then to start adding things to the ‘container’ of the novel; described above as a medicine bundle and, in the title of this volume, as a ‘carrier bag’. It’s the juxtaposition of ‘things’ that creates magic. Like an orchestra, it’s the confluence of disparate sounds that builds a symphony that is unique and moving and clarifying.

Extra, extra, read all about it: On Hardbacks.

I walked into Broadway Books the other day and picked up the new John Green hardback—and put it straight back down again, because it was £21. This is a book about the history of tuberculosis and healthcare inequity. Isn’t the point of the book itself that people who are not rich read it? Or is it aimed at the rich, who may be moved to make things more equitable? Surely people who are not rich also deserve to read about tuberculosis? Surely a book on communicable disease should be itself also be communicable, rather than prohibitively expensive? Do publishers really think a £21 rrp will help sell hardcover copies, resulting in large numbers of pre-orders for the paperback version from bookstores? This is almost 3x the minimum hourly wage for under-18s. I thought reading was in crisis? Do we not think maybe we’ve made it too expensive, and we should return to the Penguin pocket paperback era, where the paper was thin, the books were portable, and the rrp was cheap, so that we might perhaps choose between picking up a coffee… or a book? I know there are publishers and writers who follow this Substack (hi! Thanks for sticking with, while I find my stride!). What do you think? And, most importantly, how about you, readers? Would you buy more books if you could get excited about new releases and immediately go buy them without breaking the bank?

Buy Slanting Towards The Sea and Women In Love from independent bookstores (and earn me affiliate £) here.

Buy Mother Mary Comes to Me and The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction from independent bookstores here.

Thank you for taking the time to read my writing. If you enjoyed this post, felt like it spoke to you in some way, please share it via the button below or leave a comment. I really appreciate the support and your continued readership.

Buy my novels from independent bookshops here.

Find me on Instagram.

I read The God of Small Things years ago. Don't know if I'd still feel the same about it now, but I thought it was excellent at the time. It sounds and looks a bit twee (at least the British cover does), but the story itself is actually pretty brutal, upsetting in places - probably why every charity shop you went into had at least one abandoned copy!