February Reading

An undersung debut, a classic Danish trilogy, Epstein-era crime fiction, and how to choose a book

Is anybody else experiencing a reading slump at this time of year? Winter is such a treat for reading, but then after the holidays and with the lack of light, to both be writing and reading all day makes me feel somewhat restless.

Nevertheless, I do think I had a quality month for reading, if not a quantity month, and it’s picked up in the last week or so (on the downside, because I got into an accident on my Lime bike and have been attempting to rest between family time and various appointments).

Even the novel below which was not for me, I felt did have appeal for certain readers. It’s strange to say this about a book I didn’t particularly think worked, but I was glad that I read it, and I write about it below so that if you like the sound of it, you can read it too.

Perhaps it’s not that strange. I enjoy going to art exhibitions I don’t like, simply because the conversation afterwards in the cafe is always meatier. Tastes are different too—or how would we complement each other? The friend who recommended this book absolute loved it.

My reading experience of the undersung debut below was an odd one, because it was just such a good book all the way through that it reminded me of being a child and exclusively reading good books (I’m not entirely sure why this is; perhaps because the children section of the bookshop is much smaller and populated by tried and tested books? Case in point, I went into my local today and there was an entire shelf of Michael Morpurgo).

As then, I treated this book unappreciatively, not worrying about picking it up too often, because I knew that I’d like it and it was there and I could have it any time I wanted it. I didn’t savour it the way I did with Deep Cuts last year; instead I sort of pootled along with it for the first half of the month and then sank the rest in a day or so. Maybe this says more about my mental state than the book—but I suppose it’s true that, although I really enjoyed it, I didn’t love it as much as Deep Cuts.

The Zack Polanski / Green Party campaign video about running chimed so much with me. The financial pressures of my life currently stem from baby loss but also economics (and to a smaller extent various — three! — torn tendons). Perhaps that’s the reason for my slump. I find myself worrying what to add to the trick pony of work to make it actually work, and, in amongst all that bother and fuss, my mind doesn’t calm down enough to sink into a story.

[A thought: if the work that makes you money doesn’t make enough money to work, can it be called work? Note from editor—take this out, not “dreamy novelist vibes” enough. Replace with something about a bookcase, a smoking jacket, and the smell of pine in the morning.]

Speaking of work, my third read, which comes highly recommended, is set in Depression-era Copenhagen. Interesting, right from the start, as a social history as well as a reading experience.

Although I felt like a bad book lover for not finding a way to treat the debut I mention above right, I did both finish and like it so much that I added it to the pile of inspirational books I keep on my desk, which I’ll share soon. I keep these particular books close to remind me of what I want to write over the next few years. Without them, my thoughts are at risk of being lured off track by the scruffy multitude of culture that pours into my brain via my phone, confusing the issue of who I am and what I’m doing (I’m sure many of you can relate?).

I wrote early last year about my struggles with my phone. I went back on Instagram recently but I’m finding myself spending more and more time on the Discover page, and realising that it does make me feel bad to compare my life to other people’s. Who would have thought…

But should I get off it entirely? (Apart from for work, which is rewarding.) Have you slowed down or put limits on your phone consumption? I find that it doesn’t help to tell myself to put down the phone. I have to find ways to fill the negative space. What helps most is to fill life with reading and writing, friends and family.

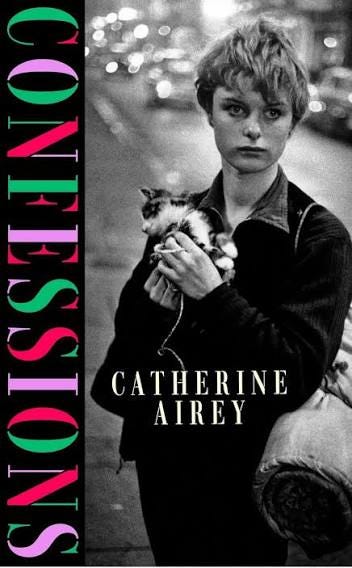

Confessions by Catherine Airey

My friend Coralie has commented in the past that I choose which novels to read in a really random way. I could blame being uneducated—and I’m sure that’s part of it. But truthfully, I’m wilfully uneducated, because I didn’t want to become institutionalised, even if it were by a fancy uni with really cool dorms, and I didn’t want to imbibe only establishment texts. Seventeen-year-old me sounds like a bit of a commie, doesn’t she? Well, I haven’t changed much.

I think there’s enormous value in questioning the given line. Who gave me this line? Who decided this was the line? Who wrote the line? Typically the answer is: rich, conservative, ignorant, white men, and as we continue to learn, over and over again, for some reason with shock, men who are pedophiles, sex offenders, abusive partners; at the least, corrupt people who got rich off the backs of people with less (economic and/or social) power.

Burroughs killed his wife. Rousseau abandoned his children. Norman Mailer stabbed his wife. Lewis Carroll took suggestive nude photos of children. Roald Dahl abused his wife. Hunter S Thompson and Bukowski were assholes. Fitzgerald was abusive to his wife Zelda. JD Salinger abused his wife and groomed an 18 year old aged 53. Social reformer Dickens was also a racist who had an affair aged 45 with an 18 year old actress and slandered his author wife Catherine. VS Naipaul abused his wife. Ted Hughes was emotionally abusive to Sylvia Plath. So many abused wives it reminds you why: feminism.

You never hear anything about the Bronte’s do you?

Social media is another kind of establishment institution. As much as I appreciate books bloggers — and I really do; I particularly like negative reviews that help me avoid wasting money on novels I won’t like, which are useful and feel bold in a landscape built on likes and false hype — other people’s opinions are another kind of line we walk. I want to walk my own line. I want to see other people walk unique lines without suggested I should do the same. It’s odd, that idea. We didn’t used to suggest everybody do something our way. But algorithms prefer persuasive posts, and that has changed online dialogue and tone.

And the establishment continue to be pedophiles and sex offenders. David Walliams (providing us with a “well that was obvious” moment) is accused of behaving inappropriately with junior female staff. Neil Gaiman is still accused of multiple sexual assaults. Junot Díaz faced accusations of sexual harassment and inappropriate behaviour in 2018. Michael Chabon faced allegations of inappropriate behaviour toward women in literary settings. Foster Wallace faced allegations of stalking and harassment, particularly toward his former partner, the poet Mary Karr, at whom he allegedly once threw a coffee table and another time attempted to push her from a moving vehicle. Cormac McCarthy, then 42, had a 17 year old girlfriend, who he (I think this is what happened—the internet is so full of articles excusing his behaviour it’s hard to discern the exact behaviour behind the excuses) whisked away to Mexico with a stolen birth certificate in order to remove her from state foster care and f*** her.

What is patently clear is that the establishment continues to protect, nurture, and reward sex offenders with £millions in publishing contracts, film options, and an abundance of platforming and legitimising — at least, until the bad publicity forces studios and publishers to renege.

Perhaps walking into a bookshop, browsing, and deciding what to read based on your own whims is a revolutionary act that centres the female gaze, egalitarianism, and choice. Perhaps letting decisions get made for you by establishment institutions is a betrayal of Catherine Dickens, Sylvia Plath, Zelda Fitzgerald, and Mary Karr.

This is how I found Confessions. In October, just before my last birthday, I walked into a bookshop with my parents and my mum suggested I pick myself out a few books for them to buy me as presents. Bizarre to say, but how twee this felt! What was this odd feeling of picking up a tome without already knowing the content? I so enjoyed it, and the two books I read, see here, that I did it again for Christmas, picking up this novel and the final book I read in February, below.

Sorry to be a basic b*tch (clearly, from the above, I’m not—sorry, that is), but I liked the cover. It was on the hardback shelf in Lincoln Waterstones. I liked the colours in the title font. The simplicity of the photo. How charming and chic is this woman’s short hair, her cat on a string? It was clear from the first page or so that I would enjoy the voice, and the setting. It opens on the moment the narrator realises her father must have died in the twin towers attack on 9/11, something I remember vividly. I hadn’t seen it anyway on Instagram, and every time I posted it to stories someone else would tell me they loved it and hadn’t seen it anywhere on Instagram either. (How does that happen?)

I like to read about things I don’t know, and people living at the centre of global, political moments, as in one of the birthday books I picked up, I will die in a foreign land. So I thought it would be about 9/11. And it really wasn’t, but I particularly enjoyed this first segment in New York, and the subsequent section in New York, and, after a while, the first section in Ireland. It’s a multi generational novel, but what is different about this conceit in Confessions is that all these generations live in the last fifty years (not unusual in terms of my own Irish family, with a tradition of having children young). I enjoyed reading life after life this way, and about modern people, with modern politics, and how they confronted the circumstances of their lives, which weren’t so dissimilar from my own experiences and those of my contemporaries (including, I imagine, you). There’s a forgivable downside to this structure, in that when you’re really into one character, you suddenly switch to another, and can feel cheated. It’s almost like you notice the author’s hand, stealing you away from the storyline you’ve just begun to love—HEY! What are you doing? I was enjoying that.

The novel opens with Cora, watching 9/11 on television. Losing her father and becoming an orphan sends her into a kind of shock. She wanders New York, not looking for him—there is no hope—but being amongst people, fed by street vendors. When her aunt Ro writes from Ireland, she must decide whether to go. We then switch to an earlier timeline, meeting Cora’s charismatic artist mother, Maire, her quiet sister Roisin, and their friend Michael, in Ireland. We learn about Scream School, a game Roisin and Maire play. Later, we follow Maire to New York, to study Art. From here, we unravel the story of their family, who is conceived and who is born and who falls in love with who, and why and how and where.

This novel didn’t necessary draw blood or tears, or elicit my deepest emotions. The experience of reading was a gentle and captivating one. I would often find myself picking up the book to read one chapter and only putting it down after many. It’s a thoughtful book. It doesn’t try to grandstand, but perhaps to meet the characters where they are, without judgement.

I’m keen to talk about this one with other people, because I want to know your best bits. It’s always notable when a book is undersung and truly loved. Why isn’t it getting the attention that other, less deserving, books are getting? It made me wonder whether, when a debut feels so effortlessly skilled, the writer is treated similarly to a novelist who has been publishing for a while. Is there just not much to say about good book that you enjoyed reading? But then, upon considering this, I realised that perhaps what a publisher might consider less marketable about this book is that it doesn’t have a particular hook. I like that. I hate hooks! I want to read a novel about humans and I want to read a novel about somebody going through something very relatable. That doesn’t mean I read solely within the bounds of my own experience, but I’m not really interested in something that happens once, due to a curious set of circumstances. Writing the biography of an illusive heiress? No, me neither. Was your party host found dead in a ballroom? Maybe for some of you not since Cambridge. Know a middle class woman who’s an atrocious mother, father somehow great? A dynamic I’ve encountered rarely if ever.

I’m not boring, but I might be tired — both personally and of the hooks that for me remove the fourth wall, and suggest this was bought by an editor who thought the marketing campaign would write itself, rather than by one who thought this would be an excellent reading experience all the way through, and take somebody who has paid £16.99 or more for a hardback away from their troubles or mundanity for a few days in a small but profound and kind of magical way.

Again, I won’t go too much into plot, because that’s so much of a book. But I will say this book contains a kind of video game (written, and sadly not on a CDROM attached to the inside back cover; how cool would that have been?), which is a conceit I love as well. Art within art. Fake narrative within a “real” fake narrative.

There were a few coincidences in the novel that I could forgive for being so coincidental because it was an enjoyable reading experience. If you like books set in Ireland or New York, this is one for you. There is a bisexual character. (These are just all my other thoughts.) Perhaps the only thing I didn’t like so much was that I found the final character, who narrates the close of the book, the least interesting. I think she is well drawn, because the child of this lineage might in fact be a quiet and thoughtful person (there were so many personalities and the stories that preceded her), but she was just not as interesting a voice for me to read as Cora, Maire, and Roisin. I didn’t dislike the character… but I did feel her voice wasn’t quite as distinct as others, and in a sense Confessions confers, as part of her storyline is about breaking away from the stories of old and trying to tell her own.

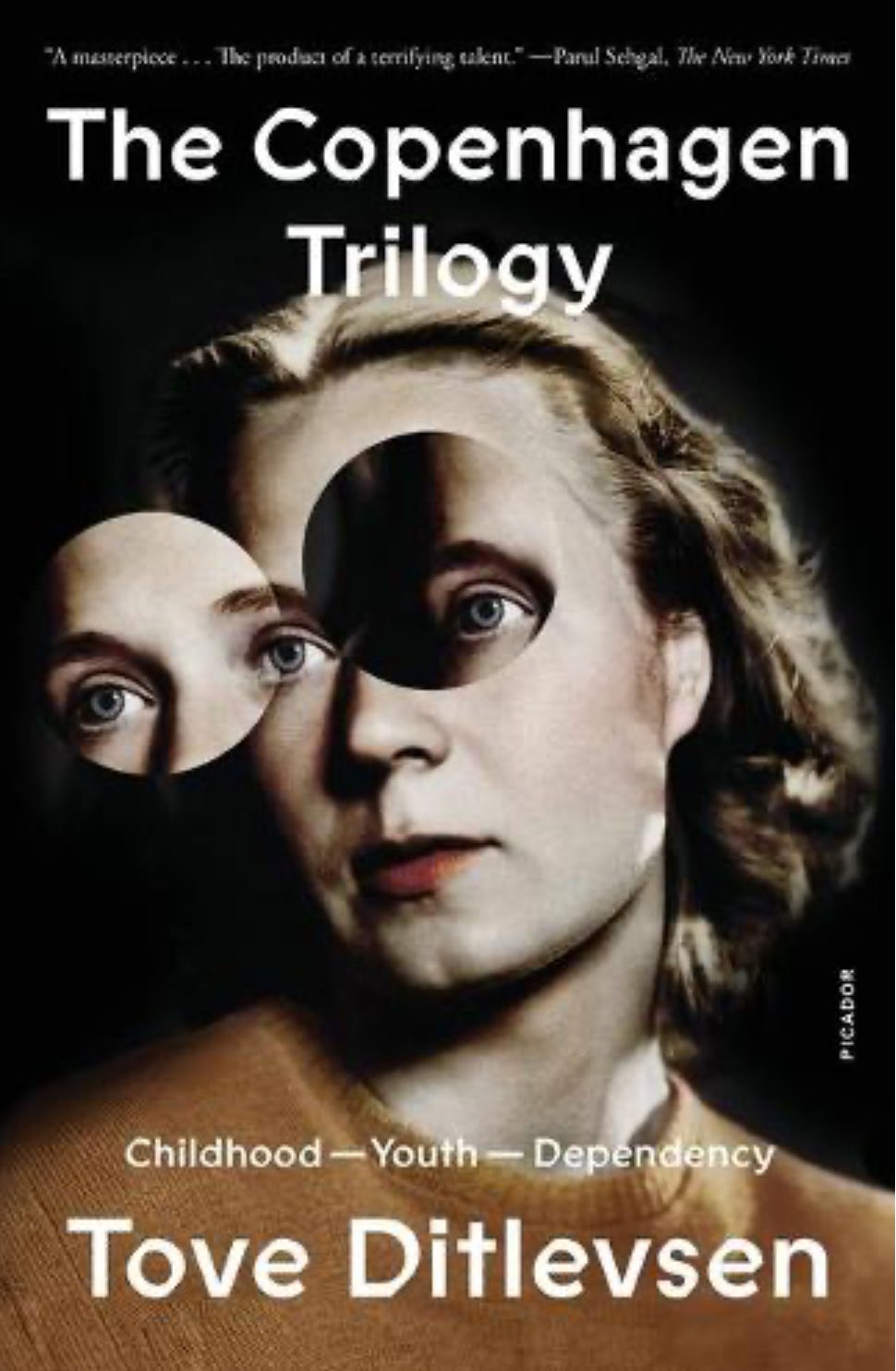

Childhood, Youth, Dependency by Tove Ditlevsen

I feel it necessary to note, given the age of this book, in fact a trilogy, that I hadn’t read it before. I picked it up in a bookshop because a car had rushed me off the road and I’d fallen off my Lime bike, smashing my teeth. I read almost all of it on the train back and forth from fens to London, to attend a hospital appointment.

Buying myself a book is my way of saying, “Don’t worry, life is real, I promise it’s not a Sisyphusean nightmare some maniacal god has purposefully trapped you in; look, have this book; there, there, try not to scream.”

As I’ve said, this is how I come across books—at random, in bookshops, in physical form, and sometimes bought to do no less than save my life, for the meantime, while I can’t do it myself.

Second to note, the review quotations on the back of this book are ridiculous. Why does the Observer reference the “darkest reaches of human experience” if not to put off readers who would enjoy reading about a young girl’s life in Copenhagen and to disappoint readers hoping to read about hell?

I think the quotations and general hype around this trilogy are the reason I waited to read this book for so long. I thought it was going to be the aching howl of a literary it girl junkie; a life doomed to the grave, full of needles and gutters and sewage and gonorrhea. Joyless and over-written. I swear to god, that’s what I thought it would be.

But no. The trilogy is a memoir following Tove, protagonist and author, who is born and lives in Copenhagen. Tove is a romantic who loves writing and wants to get married and have a baby. She’s different and an outcast because she’s writerly and doesn’t feel much with men. At a teenager, she balks at stability but desires the stability of a room to write in and alleviation from the necessity to sell her time (ie work). She’s a leftist, but she’s not out in the streets. She wants to date but talking about boys all the time is boring, and she doesn’t feel anything with most of them. She likes going out, but its draw pales compared to a warm room to read in and a typewriter and the thought that she’ll be published. She’s a dead ringer for me, and many other women besides, writers and non-writers, and I should have known this the first time I picked it up, when I thought, “gosh, there will be too much in this about going out late and shooting up. Maybe I’ll read it when I’m not feeling so in need of softness.”

More words used in the blurbs on the cover that baffle me and suggest a completely different tone: stiletto, marginalised, agonisingly compulsive, troubled girlhood, fatally wounded, thrilling.

Here are some more honest words that one could replace the above with: brogue, depression era, short, thoughtful girlhood, innocence lost, contemplative.

I’ve seen this referred to in places (including the cover image above, swiped from the internet) as The Copenhagen Trilogy, though not in the volume I have. I had it in mind to read, because I am gearing up to write the next book in my own trilogy.

Each of Tove’s three volumes (they are bound here together) is 100-130 pages and follows Tove as she grows up, from around the age of 6 into her 30s, and gradually her childhood and the innocence of youth slips away from her (but please don’t mistake, in my saying that, any implication that by the end of the trilogy she’s crawling along in the gutter holding an empty meths bottle).

In Childhood, each chapter centres on one topic or another, taking a tender, almost loving perspective on little Tove, focusing on dynamics of the family and the small world of the home.

Youth was my favourite of the three, simply because it was interesting to see how young people in Copenhagen at the time lived, and interesting to compare to Women In Love, which I wrote about last month, in terms of the romantic liaisons and social mores; these characters are the same age about 20 years later in Copenhagen, merrily shagging, divorcing, shacking up, sprogging up. Honestly apart from all the men drinking so much it sounded quite nice—certainly nicer than any modern unhoused, casual, family-less, or stay together for the kids vibes. And not that dissimilar from contemporary Copenhagen… although maybe everyone is a few years older when they have kids (internet says about 7).

Youth is also when her writing career appears in full force. Like me, she became a writer young, and she does so in a milieu of close knit literary professionals and friends (should remember next go around to marry into the fold), although mostly she just loves writing. This was so much fun to read about.

Dependency “chronicles her descent into addiction”—read simply. For me, this was such a classic story about entering into a controlling marriage (state sanctioned or common law) from a place of need (“everybody wants to use each other and that’s okay” is an idea repeated in the earlier books), where the man isolates the woman and then makes her so much less than she was to assert power over her. It was absolutely classic that a woman used to being free wouldn’t understand it as it happened, and the painkillers were only a small complication in a situation that seemed to happen all around me as I turned 30, like flowers blossoming all at once in spring.

Other Tove books translated into English: The Faces, Vilhelm’s Room, The Trouble with Happiness: and Other Stories; in older editions The Umbrella and Early Spring, and a selection of poetry (I dislike this sometimes — I’d like to buy the original collections with the authors’ choice of poem order) called There Lives A Young Girl In Me Who Will Not Die, which I have. Early Spring sounds the most interesting to me, about growing up in Denmark (the books still in print in English seem to be mostly about unhappy marriages).

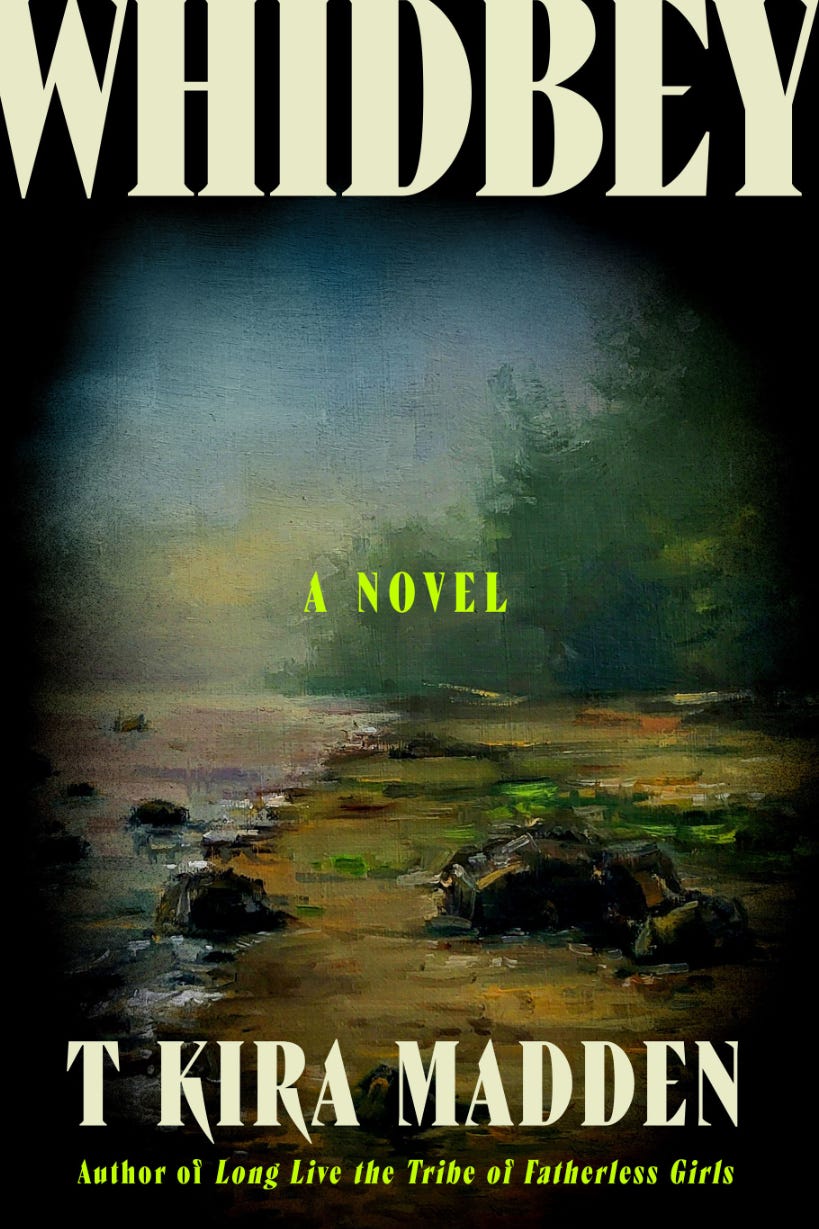

Whidbey by T. Kira Madden

This is the debut novel from the memoirist of Long Live The Tribe of Fatherless Girls—a beautiful book. I really like the writer, too, as a person (I only know her from following her online) and so I wanted to love this book more than I did. (If the writer is reading this, I apologise—but this review is just about my taste, and my bestie loved this!)

Firstly, and this is a deeply self-serving thing to say, if like me you want to read crime fiction about sexual violence against young girls / women that has joy anywhere in it at all, read my novel Dead Girls. I didn’t add funny bits or a quirky main character to be perverse or flippant about a serious subject. I do think if you’re asking somebody to read close to 500 pages about really dark topics then you should provide some levity, not only for the reader’s mental wellbeing, but because life features levity, even if soaked in tragedy. And it’s really important to tell the truth to people as a novelist. (I should write an substack post about this. It’s kind of the modus operandi for my womanhood trilogy.)

I remember hearing Madeline Black, SA survivor and author of memoir Unbroken talking about how it’s so important to hand women narratives where rape and sexual assault and abuse is survivable. Not only survivable – but something that doesn’t have to claim your joy. This was one of the things I was thinking when I read this book.

My understanding is that it’s based on the author’s experience, and I do want to be mindful of that. If you’re reading this, you probably know about my own tragedy, and obviously there are times in life when it can be difficult to see any light. But as the novel isn’t from one person’s perspective and I do think the reality is that the light is there in life, alongside grief and pain, even if the survivor can’t see it, I wanted to see that in this book. Other readers will disagree with me. And that’s why I am writing this review—to recommend it to those readers.

The novel follows three women, and for a short period of time a fourth. Birdie is escaping to self-isolation in a cabin on Whitby island, where she claims she is hiding from the man who abused her as a girl. Mary-Beth is grieving her son, the abuser, who has just been killed in a hit and run that was clearly intentional. Lindzie, another survivor of the same man, is promoting a book about the experience after telling all on reality TV.

I think the point of the book was to talk about how it is to be a survivor, and secondarily to show how unscrupulous types can use SA victims to make money. I think it did a good job of that second point for me, because I hadn’t seen anything like Lindzie’s story in contemporary fiction. I didn’t take as much away from Birdie’s story. At first I really enjoyed reading her parts of the book however, her move to Whidbey didn’t propel plot and I didn’t feel she changed during the course of the book.

Mary Beth’s narrative was, imo, much better handled. Her character was clear to me. I understood the world she lived in and how she spoke and acted with people, so considerate and protective of her son and so despising of her sister, aware at all times that she is looked down on as someone whose life skirts the line of poverty and accessibility. I did see how it might feel to be her, a mother of a person who did the things her son did, which I appreciated. Her situation was immovable, and even if her belief in her son’s innocence was far-fetched, it was believable how she would feel as she did—ferocious and denying. She had no real other choice. It’s very hard to give up on your children. Mary-Beth’s sister was also a fantastic character. No holds barred, I felt they were both very well drawn. I understood why they did what they did and who they were to themselves and others. There was a lot of plot in this part of the story, and I appreciated it. Both women were active in the story, too, and so it was interesting to read along, wondering what action would slither from their twisted worldviews next.

Cal, Mary-Beth’s son, was less defined as a character for me. One novel that sketches a perpetrator really well is Winnie M Li’s thriller Dark Chapter, based on the author’s own experience of a stranger rape in Ireland, in which alternate chapters tell the story of survivor and perpetrator, from their point of view. Highly recommend that one. More commercial than literary, it’s a smart, well-written page turner.

Lindzie’s character is seen first in the novel through the eyes of Birdie, so it’s no surprise that when we switch to her chapters the character completely changes. However, this was really jarring to the read, particularly as they were in touch as children. It seemed to me that if Birdie knew her well she should have known that Lindzie could not write that book. She did not appear to be a very articulate person, and yet the sections of the book that Birdie reads early on in the novel read like investigative journalism from an SA survivor turned activist.

The following comment is both a recommendation of sorts and why Whidbey didn’t completely work for me. It is beautifully written on a sentence level. Literary readers in it for thoughtful writing will not be disappointed. But when the character was not distinct, this meant I couldn’t see beneath the beautiful writing to find out who they were.

Birdie comes from Florida and doesn’t seem remarkable well to do; she’s a cinema projectionist, and yet her voice, her narration, is never casual. The language she uses is always worthy of the best of literary fiction. Her chapters were well-written—but she struck me as an emotional and erratic person, and I would have liked to see her rendered in colour rather than the one-note, somehow detached version of her we get. I think it would barely have made a difference to the wording of the chapters had they been in the third person, and, to me, a character’s voice is so distinct, their perspective so unique, that using first person should change not only how things are perceived and described to the reader but what happens. I felt I couldn’t see who Lindzie was either—she was brushstrokes but not a whole painting.

One thing missing from this review is a discussion of the plot. There was a decent plot there and given the plot is a large part of crime, I just won’t give anything away by talking about it. Take it from me – there is plot! Stemming, of course, from the hit-and-run that kills Birdie and Lindzie’s abuser.

I do wonder whether I would have enjoyed this much more in my late 20s. Then, I was completely into crime fiction, listened to true crime podcasts all the time, and watched every Scandinavian crime drama going (still do that last one, can’t miss some gorgeous blonde in a cuddly jumper swing her hair about, act moody, raise a child alone, and be better than everyone else at detective work for no reason). I think before I lost children, I wanted to read about pain. That sounds so raw to write, but it seems to me that there is an impulse when one is young to want to look deep into the dark. And then sometimes you find yourself in an era when life itself depends on reaching for the light.

That’s my experience. And of course it doesn’t negate the author’s, or anyone else’s. It’s not entirely true either because I know that sometimes you have to feel, and reading about fictional people who are going through the things that have happened to you can be really helpful, in helping draw out tears that need to fall. What I’m trying to say is that if you’re reader that loves dark crime fiction without joy, you may well love this book (the ceaseless pain reminded me of A Little Life, which obviously was a ginormous bestseller). If not, read Dead Girls (by me) which I did write in my late 20s true crime era and which I did not make solely about the dark—but, I suppose, about fighting it (and which wasn’t a bestseller; not even close).

Sidenote, I also think this is coming out at the right time for a renewed conversation about SA — partly because of the release of the Epstein files and partly due to the upcoming ten year anniversary of #metoo.

Like the sound of these books? Buy any of them here, to support both independent bookstores and my work.

Thank you for taking the time to read my writing. If you enjoyed this post, felt like it spoke to you in some way, please share it via the button below or leave a comment. I really appreciate the support and your continued readership.

Buy my novels from independent bookshops here. (Every sale supports my work, as I earn commission on them at no extra cost to you.)

Find me on Instagram.